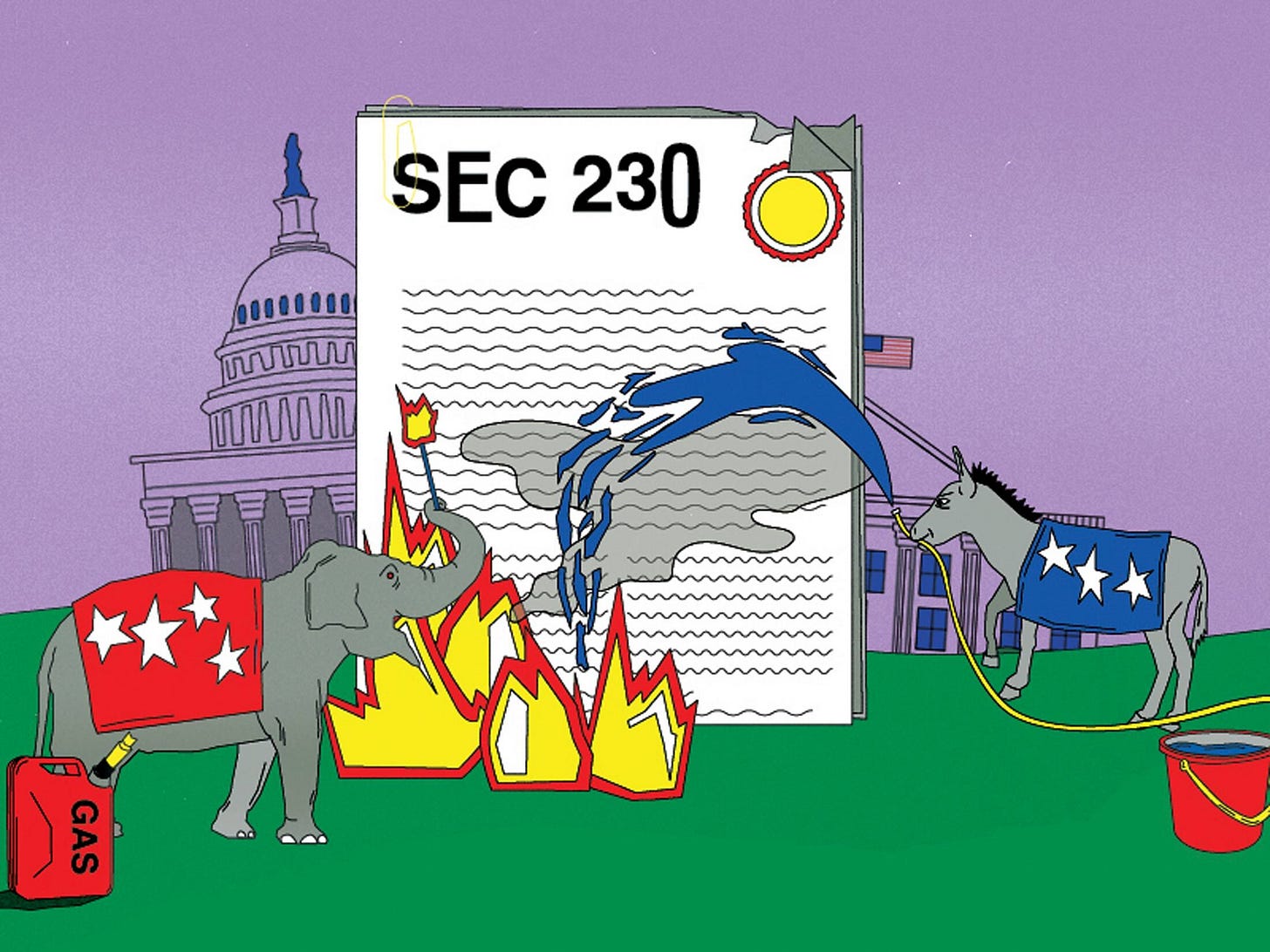

How an outdated internet law is helping disinformation spread online today

This is the story of Yury Mosha and how Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 is harming him and his business.

The big story

Yury Mosha reached out to me after reading last week’s newsletter about President-elect Joe Biden and the need for his administration to immediately reform technology laws in the United States.

In that piece, I mentioned Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a law that provides immunity to internet platforms like Google, Facebook, and Twitter from being treated as the publisher of any information a user provides, protecting these companies from lawsuits. In essence, the law means that these companies have no accountability when it comes to the content published on their platforms, which means disinformation can spread without any repercussions.

Sometimes when we talk about big, abstract tech ideas, we fail to understand how they actually affect everyday people. So, this is the story of Yury Mosha and his business Second Passport, and it provides a clear demonstration as to how a law from the days of dial-up internet is harming people and businesses today. While it will be surprising for some, Mosha’s story is a familiar one that happens to thousands of people around the world every day.

Mosha started his business Second Passport in 2011 after immigrating from Russia to the United States. Second Passport helps Russian-speaking immigrants in 80 different countries obtain visas and more smoothly transition to a new country. Per their press release, “Second Passport has serviced over 5,000 clients as they focus on assisting their clients in gaining citizenship, residence permits, work and education services in countries all over the world.”

Recently, however, Mosha has been the subject of online news articles published on criminal websites that are untrue and meant to slander and tarnish his brand. He believes his Moscow-based competitors (in immigration services) have paid to have these articles published about him for the sake of market competition. After all, there is a multitude of criminal websites that exist purely to publish false information, and they often extort and blackmail the victims of these fake articles. A few examples of these sites are: http://stophish.ru/, http://trashik.news/, and http://fbi.media/ (they are not secure, so I would recommend against searching them). In fact, it is incredibly straightforward to purchase negative PR on a person or company: All you have to do is Google it.

Fake news can tarnish a person or business’s reputation within minutes of being published. According to Mosha, who spoke to me on Zoom through a translator, “I lose about 50 percent of potential clients yearly, and that ends up being thousands and thousands of dollars that I am losing because [when] people search up information [on me], they find these kinds of sites, and people are gullible, they believe it, and they don't want to work with him anymore.”

Mosha contacted these websites to take down the slanderous articles about him, and they said they would do it… for a price. However, the owners of these websites are anonymous, and once they are aware that one is willing to pay to have content taken down, they will often continue to blackmail you. Plus, even if Mosha had paid to have them take down the articles, his competitors could just purchase more articles, so it’s not a permanent solution.

Consequently, Mosha sought legal help and his lawyers advised him to purchase reputation management services, which is basically positive PR that will appear higher up on the Google search engine, pushing the negative, slanderous articles further down. However, this is another temporary and expensive solution.

After Mosha went to Russian court to obtain legal paperwork stating that their articles were false and slanderous articles about him published on criminal websites, he contacted Google, the platform that these sites exist on and the search engine on which they are indexed. Google — citing Section 230 — claimed that they were not legally responsible for the content published to their platform and were therefore not going to do anything about it.

Section 230 is unique to the United States, of course. It was created in 1996 during a time of dial-up internet and is widely outdated considering how fast technology has progressed and how big of an issue misinformation has become.

In Europe, The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) from 2016 forces internet providers to take responsibility when it comes to the content published on their platforms, and they get huge fines if they don’t. According to Mosha, the only way these big tech companies will actually listen is by putting their bottom line in jeopardy.

Joe Biden spoke to The New York Times prior to being elected and said that Section 230 “immediately should be revoked.” However, even if Biden is willing to keep his word, a revoke or repeal of Section 230 will need to go through the House of Representatives and then the Senate, which is one of the many reasons that the two run-off Senate races in Georgia in January are so important.

In the United States, Mosha has contacted all of the Congressmen in his home state of New York and about 100 Senators across the nation about the need to repeal or at least reform Section 230. He has received responses from five Congressmen and two Senators.

“I really just want to bring more awareness for this, to get people involved,” says Mosha. “I also want to urge people to reach out to their Congressmen, to really get all government officials involved in this and kind of speed up the process, because there is really no other way to fix it… And it's a really big issue, you know, we are in the 21st century and the fact that these laws are so outdated is kind of ridiculous at this point.”

The following are Mosha’s suggested changes to Section 230:

1: Make social networks and search engines such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Google, and others have departments specifically dedicated to filtering what is fake news and what is not. As soon as they identify something as fake news, they need to delete this content, these accounts, and these fake sites.

2: If a person has a court decision from a foreign government about something being fake news, these social platforms need to recognize this as valid. There needs to be an understanding of a global court of law about fake news.

3: When contacting social platforms about fake news being published, these platforms need to respond in a timely manner. In three days, for example. Fake news being spread can do damage very quickly, and often by the time the platform responds, the harm is already done.

4: If Google and other search engines do not delete this false information, then they have to pay large fees. This will serve as an incentive for them to actually delete wrongful information, as they will be motivated to not pay large sums of money.

Notes

Question (please respond in the comments)

Has anything like this ever happened to you or someone you know? Did they resolve the issue?

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll share it with friends using this link:

And subscribe to get the newsletter delivered to your inbox for free using this link:

I’m always looking for writing work! If you have any leads, email: orenweisfeld@gmail.com or DM me on Twitter: @orenweisfeld. My published work can be found here.

My cousin had a business page smeared by fake posts that showed up first in search results, and it tanked their bookings for months. You could try Loyally AI to push verified customer success stories and a loyalty program that surfaces real experiences. Within weeks their online reputation looked more normal and calls started coming back, not perfect but way better.